#010 - Designing Dynamic Game Music Systems - with Pav Gekko

Pav Gekko shares how he designs interactive music systems that react to gameplay and enhance player experience using Wwise and Unreal Engine.

Welcome to Quick Dev Insights. A series of bite-sized interviews with people who work in and around the games industry, from indie to AAA. A full list of these interviews can be found here. Find out when new ones are released by subscribing below or following me on Twitter.

Designing Dynamic Game Music Systems

with Pav Gekko

Introduce yourself

I’m Pav Gekko, a British-Polish freelance composer and audio director working in games and media. I’m a BAFTA member and a 2025 Music+Sound Awards finalist in the Gameplay and Cinematics categories for Spirit of the North 2, alongside titles like Star Wars Outlaws, Overwatch 2, Indiana Jones and the Great Circle, and Assassin’s Creed Shadows. The game features my score and the interactive music system that I designed from the ground up.

One of my recent live projects involved recording with a Midlands-based symphony orchestra to celebrate live musicians in game music. A project that was featured by IGN, PlayStation, and Xbox channels. It was based on my fairytale-inspired, neoclassical score for Smalland: Survive the Wilds.

Outside of games, my music has been featured in TV shows such as Mythic Quest (Apple TV), Kung-Fu (HBO), and Rings of Power: Behind the Scenes (Amazon). I’ve also won the Midlands Movies Best Score Award and was a finalist for Best Music Artist at the 2025 We Are Creative Awards.

I’m passionate about the art of scoring and storytelling through music in games - not only the harmony, arrangement, but also the technology behind it. I love exploring how tools like Unreal Engine 5, Wwise, and other middleware can work together with composition to create deeper emotional experiences in games.

What creative possibilities does Wwise open up when working with music in Unreal Engine?

Wwise allows for designing highly interactive music systems that are closely tied to gameplay - music that reacts to what the player is doing by switching tracks, playlists, or layers in real time and syncing precisely to player movement or game states. The beauty of Wwise is how simple it makes this process.

In theory, you could build all of this from scratch in Unreal, but it’s a bit like asking whether you should build your own game engine instead of using Unreal or Unity. Creating and maintaining a custom system takes enormous effort, while middlewares like Wwise has already refined and streamlined these workflows through years of real-world use and iteration across many games.

For example, creating a day–night cycle system in Wwise takes just a few minutes - importing audio, defining a Day/Night state group, and tying it to a SetState function in Unreal. Quick and simple.

Wwise offers a well-designed API and a standardized set of modules that let you build extensive state machines, expose parameters to Unreal, switch layers or tracks, and adjust the mix - all within an intuitive user interface. I mainly use Wwise because I’ve worked in it for years, and it’s become second nature to me. However, this can be achieved in other middlewares too.

See Pav’s dynamic music system in action in Spirit of the North 2 in his YouTube video

Once the structure and parameters are set up in Wwise, Unreal can communicate with it through functions that change states or send real-time parameter values. This setup makes it easy to iterate on both the music and the systems - you can test everything outside Unreal, simulate gameplay conditions, and refine transitions without constant re-imports.

Middleware tools like Wwise and Fmod provide a standardized, flexible framework that speeds up production, makes iteration easier, and allows larger teams to collaborate efficiently since the workflow is widely understood across the industry. And because of this you can build more interesting, more complex systems and push the boundaries of interactivity.

When designing a dynamic music system, how do you plan the overall structure?

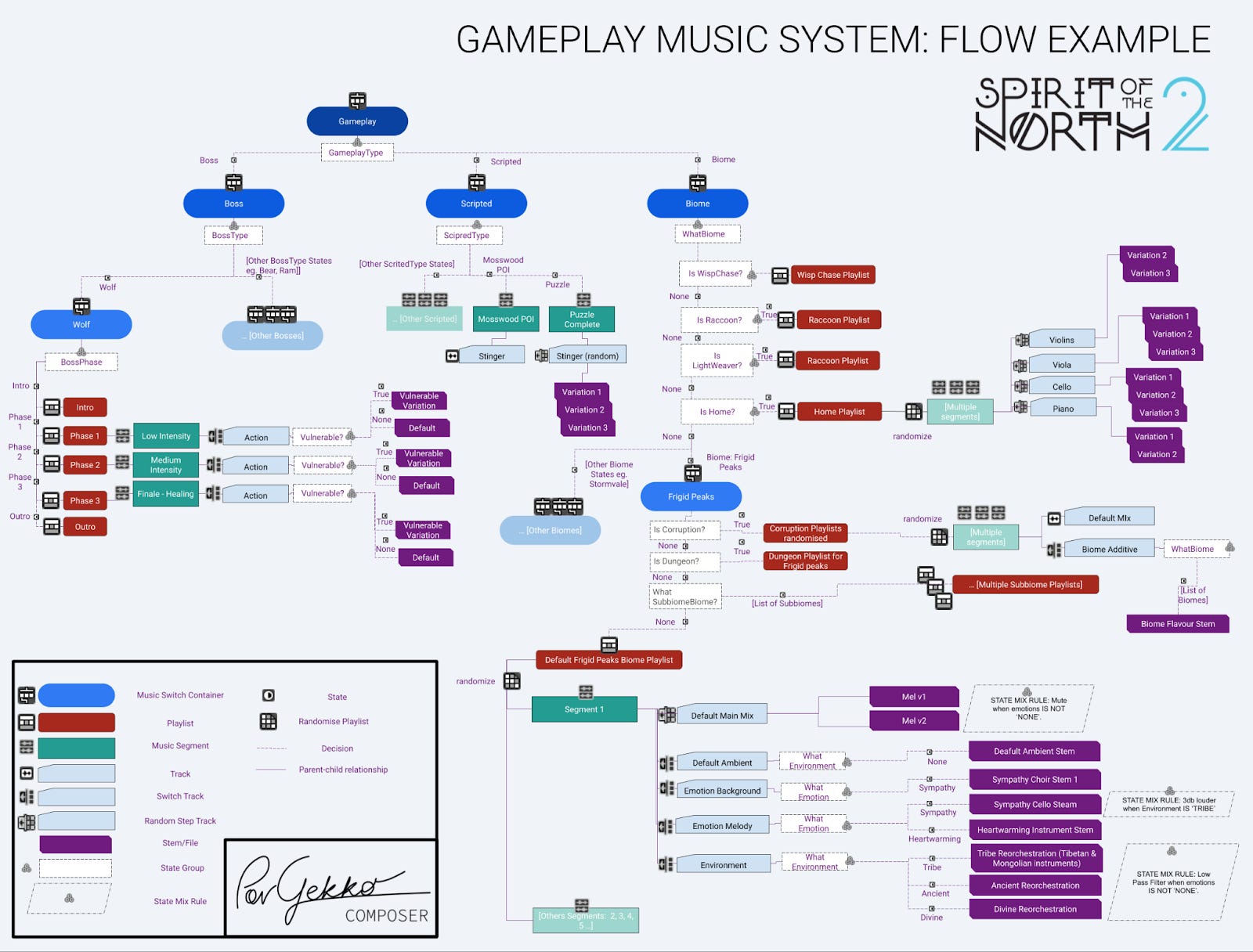

For me, the rule is always “Gameplay First”. The first step is to identify the key gameplay elements and the unique selling points of the game - what makes the player experience special. Music should serve as a tool to enhance those moments, much like art does.

At a high level, I look at the game’s structure: are there distinct modes such as combat and exploration? Within combat, are there sub-systems - for example, different enemy tiers (easy, mid, hard) or bonus streaks that reward skill? Maybe the focus is on performance feedback, or perhaps, like in Spirit of the North 2, the goal is for the music to tell the story - to tag different parts of the world with emotions that shift seamlessly in real time.

Once I know what defines the player’s experience, I move to Pen And Paper. I sketch a diagram to visualize how the music will behave - what types of transitions or changes I can use, whether it’s a stinger, re-orchestration through switch tracks and layers, or a full playlist change.

From there, I create a Cue Sheet - a spreadsheet that lists all the required music assets. It’s like a checklist for me as both composer and audio director, including the number of stems or layers I need to export, and also creative notes about tone, tempo, instrumentation, and emotion.

I’ll then compose short placeholders or use existing material and build the system in Wwise to Prototype And Test It Early. This lets me verify that the Wwise and Unreal integration works as intended before producing the final score. From that point on, it’s all about Iteration, Tweaking, And Debugging - refining both the system and the music until they feel perfectly connected to gameplay.

How does writing for a dynamic music system change your approach to composition?

Writing for a dynamic music system completely changes how you think about composition. The technical requirements are very different from writing for film or cinematics. In linear media, you follow what’s happening on screen and enhance those moments - you don’t have to worry about transitions or looping, and you can take more harmonic freedom.

In gameplay, it’s different. The music has to act like a snapshot in time - it represents a specific mood, emotion, or energy, but needs to stay relatively stable so it can adapt smoothly to gameplay changes. It still needs to stay interesting, but without dramatic buildups or sudden harmonic shifts. If you change harmony too much, you risk mismatching the player’s experience, because the player might not be emotionally in the same place as the music anymore.

Another big requirement in games is that the music often needs to change almost instantly - for example, when a player enters combat, discovers a secret, or triggers a new boss phase. Transitions must be both musical and technically seamless. The goal is to keep the music within one “musical world” that matches the player’s current action, and then move to another cue specifically designed for the next state.

Large harmonic or orchestral changes work best when they’re tied to interactivity - for instance, in Spirit of the North 2, the music changes key and increases orchestral intensity as the boss evolves from phase one to two. Writing this way is an exercise in restraint, requiring strong orchestration and production skills to stay in one emotional zone while keeping the listener engaged.

When working with switch tracks, sometimes I write music that can still function if certain instruments drop out or are added - for example, bringing in cellos to add melancholy or removing them to make the atmosphere lighter.

Transitions are another key consideration. It’s easier to switch cues instantly if the music doesn’t stray into complex harmonic territory that takes time to resolve. I solve this during the writing stage - either by composing transition segments or by composing in related keys and tempos to make transitions seamless. It’s always a balance between musical intent and technical practicality.

In Spirit of the North 2, instrumentation itself helped smooth transitions. Nearly every track began with an ambient drone layer (from ebow guitars, delicate string textures etc.) that acted as a “gel,” blending cues naturally.

How do you collaborate with the rest of the team to keep music and world-building connected, and what tools help you debug and maintain a large dynamic system?

From the very beginning, I work closely with the game designers to understand what makes the game tick - its core mechanics, emotions, and unique qualities. That becomes the foundation for the entire music system. My goal is always to enhance their vision, but often, the music system itself also inspires design ideas, which makes the process feel truly collaborative and creative.

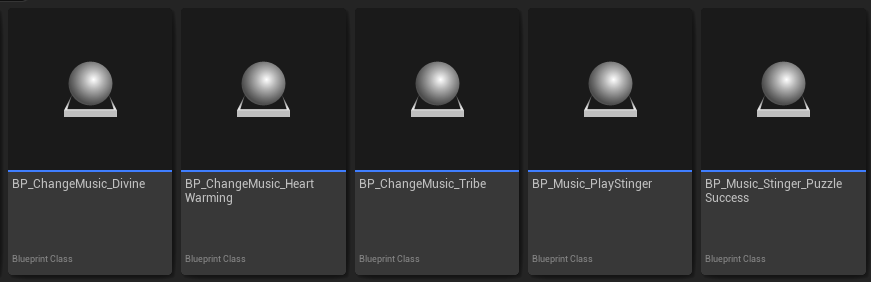

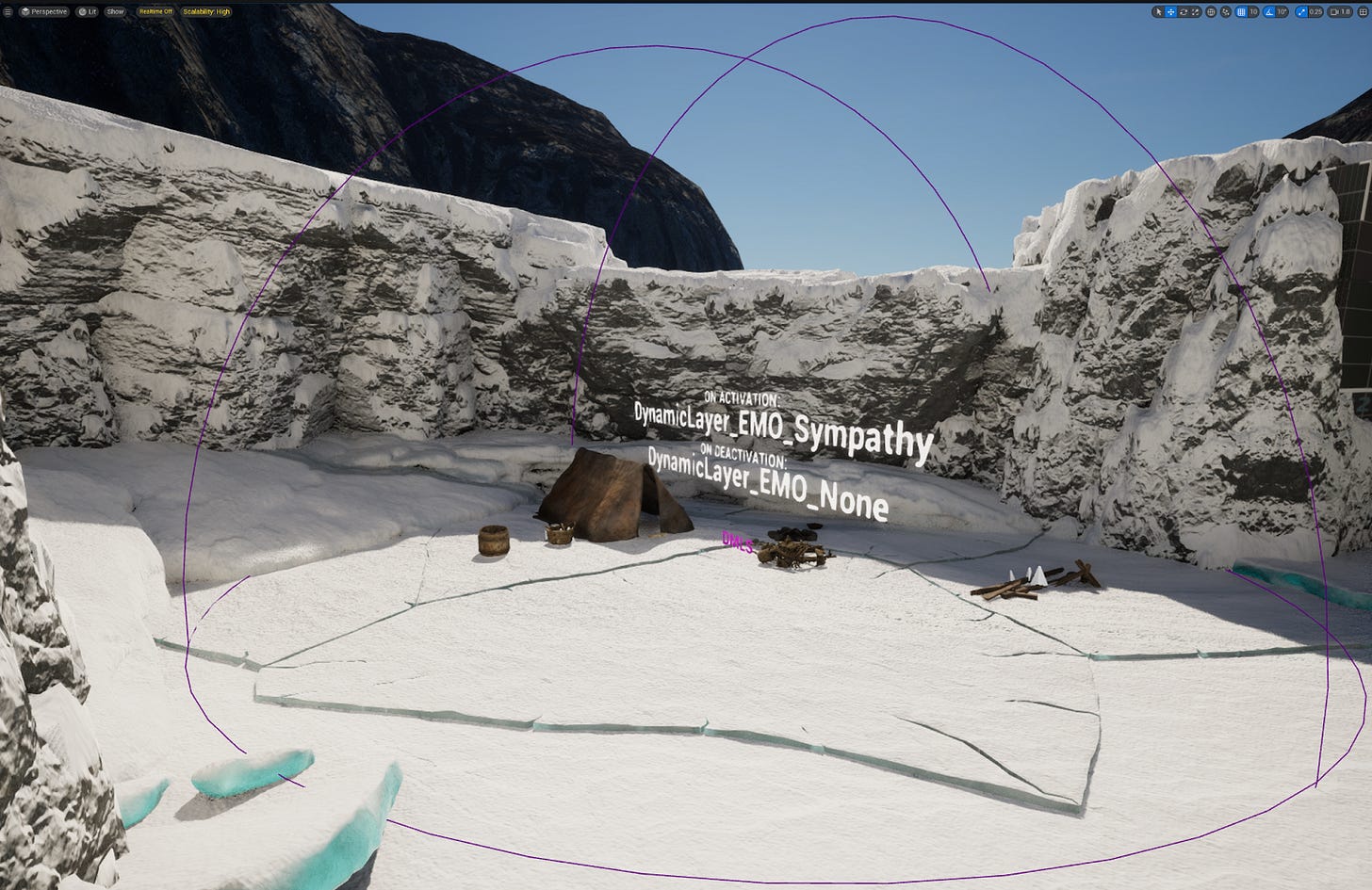

During production, it’s important to educate the team about how the system works and to make it as streamlined as possible so everyone can use it to enhance the game. Although I usually handle the implementation - modifying existing blueprints, testing, and iterating within Unreal - I make sure I’m not a bottleneck. The system should empower others, not depend solely on me.

For a large open world like Spirit of the North 2, it would have been impossible for the audio team alone to play through 40+ hours of content and manually tag every cave, ruin, or vista for musical cues. The solution was to create a set of simple Unreal blueprints with built-in box triggers - things like BP_ChangeMusic_Sympathy, BP_ChangeMusic_Tribe, or BP_ChangeMusic_Vista.

Designers could drop these triggers directly into their levels during world-building, effectively tagging the environment with musical meaning. They didn’t need to know Wwise - just think emotionally: Should this space feel awe-inspiring, sorrowful, intimate, or dangerous? This approach made music part of the level design language, ensuring emotional storytelling in the world was instantly reflected in sound.

In a longer game, how do you keep the music feeling fresh and avoid listener fatigue?

I approach this on two levels: compositional and technical.

On the compositional level, my main goal is to keep the music interesting through variety in orchestration and instrumentation, while staying within the same harmonic framework.

A lot of interest comes from presenting the same material in different ways - using different inversions of chords, exploring open and closed voicings, and reassigning them to different sections of the orchestra. This gives the player the sense of progression even though the chord progression stays the same.

On the technical side, variety comes from interactivity and randomization. You can swap playlists, add or subtract layers, or introduce random switch tracks. In Spirit of the North 2, Wwise introduced variation at multiple layers:

Randomized segments within playlists ensured cues never looped identically.

Random switch tracks created subtle differences - for example, puzzle completion stingers sounding slightly different each time, or the Mosswood biome melody being played by a different instrument on each loop.

Where can people find more of your work?

For music composition or sound design enquiries, the best way to reach me is through LinkedIn or my website.

I’d love for you to have a listen to my work - the Spirit of the North 2 Original Soundtrack is currently available on YouTube, and will soon be released on all major streaming platforms.

If you’re interested in behind-the-scenes insights, tips, and ideas about music and interactive design, please follow my YouTube channel. And as awards season begins, please keep your fingers crossed for Spirit of the North 2!

🌐 My Website: www.pavgekko.com

🔗 All my social links: linktr.ee/PavGekko

📝 Read my in-depth article on Wwise techniques: Driving Narrative and Emotion Through Music Systems – The Interactive Score of Spirit of the North 2